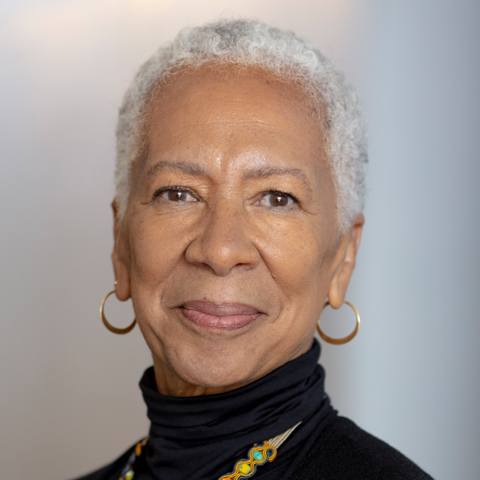

Building a Caring Economy: Angela Glover Blackwell in Conversation with Ai-jen Poo

Activist and MacArthur "genius" award winner Ai-jen Poo is leading a movement to reshape America’s fastest-growing industry — home care — to create millions of good jobs and provide high-quality services for seniors and others who need assistance. Her new book, The Age of Dignity: Preparing for the Elder Boom in a Changing America, explains how to harness the nation’s age wave to build "a caring economy" that benefits everyone: the rapidly aging, largely White population driving up demand for care, the workforce made up largely of women of color, and the nation as a whole, struggling to grow wages and the economy. PolicyLink Founder and CEO Angela Glover Blackwell spoke with Poo about her vision and strategy for equity-focused change in a sector vital for economic growth, especially in low-income communities, and for the health and well-being of all.

Angela Glover Blackwell: So many Americans are struggling with how to care for their parents and grandparents. Politicians and the media speak of the elder boom as a crisis, but you’ve described it as a blessing, as a way to create economic opportunity for our nation’s other rapidly growing demographic, people of color.

Ai-jen Poo: The fact that people are living longer is an opportunity for people to connect longer, work longer, play longer, love longer, learn longer, and contribute longer. This is a paradigm-shifting moment, an opportunity to strengthen multigenerational relationships. It’s also clear that we need to rethink our health care and long-term care systems in order to support people to live independently and to age in place, which is the preference of 90 percent of Americans. That offers enormous opportunities to create millions of jobs in home care and long-term care and to transform what’s now low-wage work into good jobs that you can take pride in and support your family on. Caregiving is a unique place where we can all come together and benefit a huge, broad cross-section of our population. It’s a win-win for more choices, better quality care, and better jobs for the future.

Blackwell: You write that caregivers are largely invisible and their work is often degraded. That’s the opposite of what one would hope for when we think about people caring for those we love and cherish. Why isn’t the work — or the workforce — valued more highly, and how does federal policy feed the problem?

Poo: We have a long history in this country of undervaluing the work that goes into raising and supporting families, and our legacy of racism and slavery has shaped our labor protections. The clearest example is our flagship legislation for protecting workers, the National Labor Relations Act, and the Fair Labor Standards Act, which were enacted during the New Deal. Southern members of Congress essentially refused to support New Deal labor protections if they included farm workers and domestic workers, who at the time were largely African American. So the legislative package passed with those exclusions. Over the years, domestic workers, home care workers, and farm workers have fought and organized to eliminate those exclusions and establish standards and protections, but the exclusions remain to this day. The law defines home care as companionship, akin to babysitting, as opposed to real work. The truth is it takes tremendous emotional intelligence and skill to do this work well, especially when it comes to caring for elders who may have complex medical conditions and needs. We’ve been working diligently with the Department of Labor to change that anachronistic definition and bring two million home care workers into the protection of the minimum wage and overtime laws.

Blackwell: You argue for a comprehensive federal policy of caring. What does that look like? What investments are needed?

Poo: We need to think about taking three major courses of action. One: elevate the quality of home care jobs. That requires a suite of policies, from raising wages to ensuring health-care access to providing access to training and career ladders. Two: we need policies that ensure the affordability and accessibility of quality care. Right now, if you're very, very wealthy you might purchase long-term care insurance and if you're very, very poor, you might be eligible for Medicaid. But millions of people in the middle are struggling with how they're going to meet their care needs. We need a framework that supports working families, including caregivers themselves, to be able to afford the care they need, at a really high quality.

And that brings us to the third course of action. We need to create new care choices for people. The predominant model is institutional — the nursing home. We want to make sure that we can bring high-quality care to every American home, and that every home has the opportunity to choose the care that is most appropriate for that family. To move us toward a vision of good jobs all around, affordable high-quality care, and maximum choice requires investment in caregiving as a vital aspect of our society's well-being.

Blackwell: Those are extremely good goals. And I have seen in the past that when jobs become good jobs, the people who have traditionally held those get pushed out and often don't have the pathways into training and credentialing. How do we make sure that the elevation of the caregiving job goes along with the elevation of the people who have been doing the work?

Poo: I'm so glad you raised that because it’s something we think about a lot. One piece is the prioritization of training and rethinking workforce development systems from the bottom up. So we are developing training for domestic workers in different aspects of long-term care, everything from mindfulness training for caregivers to specialized training for people working with people with dementia and Alzheimer’s. We really believe that domestic workers — who are on the front lines of what families and individuals need in order to live dignified, healthy lives — have incredible insight for us about how we rethink training. And we’re listening to what workers say about the training they want and need. We're asking them to inform the substance, the methodology, and the delivery of the training so we democratize access.

Blackwell: Are there good models of local policies or initiatives that are moving us toward creating a caring economy? Things that we can learn from and bring to scale?

Poo: The State of Washington has a home care training fund that trains 40,000 home care workers per year, in 12 different languages. It’s a beautiful model that’s both elevated the quality of care for seniors and the quality of jobs for workers. Hawaii this year will introduce a long-term care insurance program to provide families with support for their long-term care needs. Maine’s Keep Me Home Initiative is the Speaker of the House’s vision for a comprehensive policy package to support seniors who are aging in place. And it includes everything from rethinking transportation to higher wages for home care providers. And of course we need to keep working hard at establishing and securing basic rights for the workforce. We’ve won Domestic Workers’ Bills of Rights in four states. We’ll be working in Connecticut and Illinois to continue to build momentum state by state.

Blackwell: One of the things that has impressed so many of us in the equity movement is the care, connectedness, and authenticity of your work. You are building a movement across race, region, and generation. What strategies have been most effective in building alliances and bringing together workers who generally labor in the privacy and isolation of the home?

Poo: We strongly believe in the power of storytelling, not only as a tool for bringing people together but really as a way for us to reimagine the kind of power we have when we come together. In 2011, we started organizing Care Congresses, multiracial, multigenerational gatherings of hundreds and then thousands of people in cities around the country to talk about a vision for the future of caregiving that uplifts the dignity of workers and the families and individuals they support. And we began every gathering with people turning to the people next to them and sharing a story about somebody who took care of them in their lives and the value of that relationship. It rooted all our work — policy, organizing, elections work —in the context of the values and the stories that are so closely held in our lives. Recently, at Caring Across Generations, we also engaged with The Moth, an arts nonprofit wholly focused on the power of live and personal storytelling. So often as organizers or experts or leaders, we describe other people’s stories but there can be a unique impact when you hear someone’s story told in their own voice. It can also be an incredibly empowering and connecting experience for the storyteller. This grounding in our experiences has allowed us to create an incredibly human movement culture. It also opens up possibilities for us to connect very diverse experiences in a way that doesn't erase our differences but builds upon the power of what we share.

We learned a ton from PolicyLink about the opportunities of equity and about new ways of thinking about solutions in the midst of all this change in our country. We share with the equity movement a strong commitment to elevating low-wage workers as protagonists in shaping the future of the economy. It is no longer just about how we gain one dollar more per hour or one or two more sick days per year. The question is, how do we shape the future of this economy in a way that transforms opportunity for low-wage workers and that transforms the character of the work itself? The experiences of workers — people struggling with control over their hours or with sexual harassment or stretching their paycheck to be able to feed their kids — their experiences and insights are leading us into a future that is much more equitable and humane. This is a moment to change how this economy is structured in a way that benefits all of us.