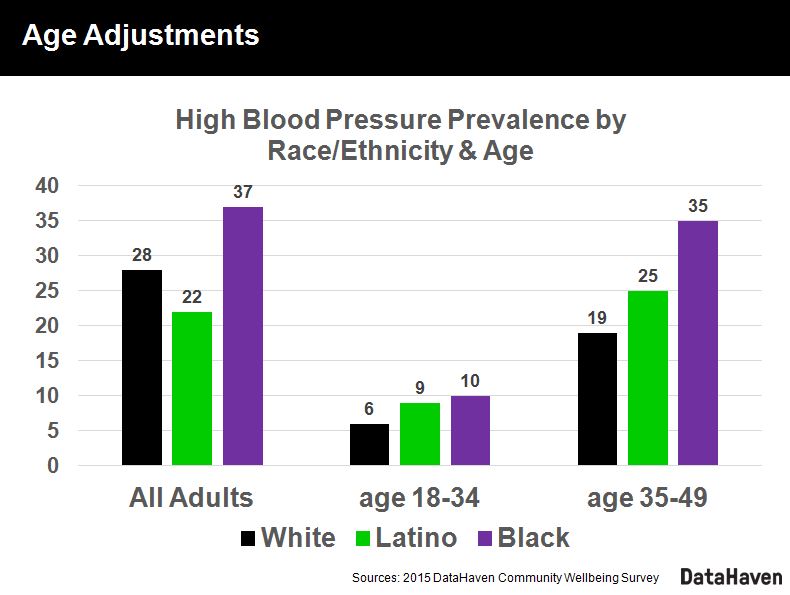

Twenty-eight percent of adults who identify as non-Hispanic white in Connecticut report that they experience high blood pressure, compared to twenty-two percent of adults who identify as Latino, according to DataHaven’s 2015 Community Wellbeing Survey. This statistic suggests that for this health measure, Latinos fare better than their white counterparts.

However, the median age of white adults is more than a decade higher than the median age for Latinos in Connecticut. If you examine age-specific rates comparing whites and Latinos within the same age groups, Latinos experience high blood pressure at significantly higher rates.

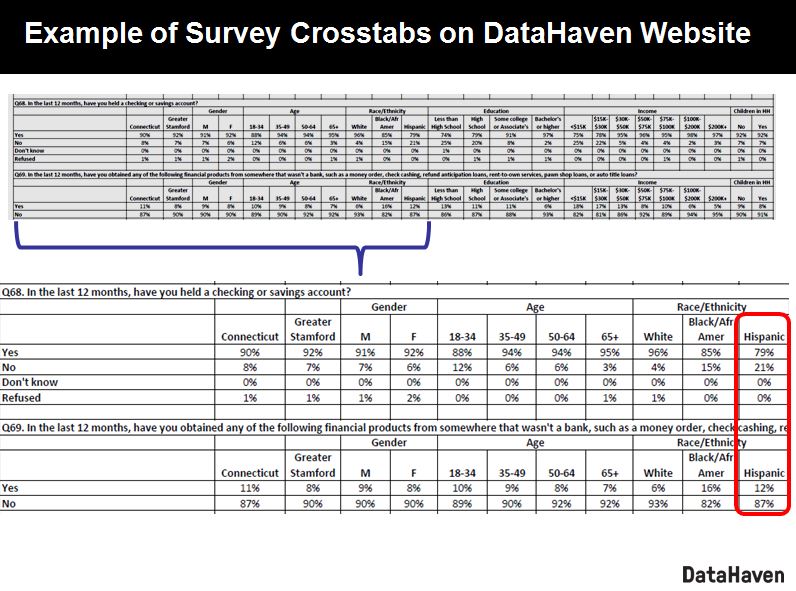

This is just one example of the importance of breaking down data by age, race and ethnicity, neighborhood, income, and other factors. By providing community profiles, crosstabs, and public reports of the data collected from its Community Wellbeing Survey as well as other sources, DataHaven and its partners aim to emphasize why examining local data at multiple levels is necessary to making accurate, informed policy decisions that improve well-being and overall quality of life.

Well-being measurement as a unifier

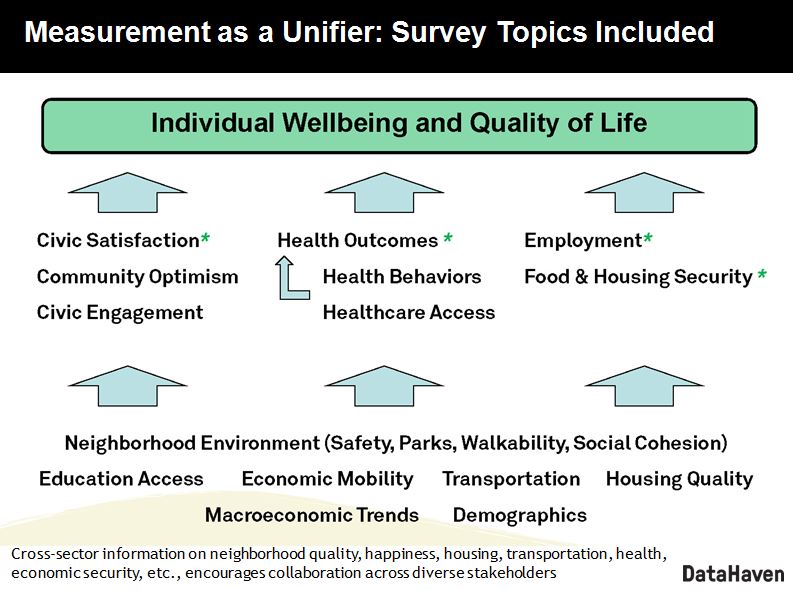

The DataHaven survey supports organizations working across different issue sectors, allowing them to understand how issues such as employment, financial stress, health, transportation, and neighborhood quality are related to one another.

To facilitate this, the survey includes a series of questions designed to measure happiness, physical and mental health, and life satisfaction – also known as experienced and evaluative well-being – that were based on well-known international surveys.

These desired “well-being outcomes” are presumably shared by all people working to improve quality of life within an area; measuring them is a way to show how such efforts are interconnected as well as helping to reveal some of the largest barriers to individual well-being.

According to our analyses, some of the barriers that stand out include a lack of social or community support, inability to afford needed health care, under-employment, and food insecurity.

According to Anita Chandra, Director of RAND Infrastructure, Justice, and Environment, one of the advisors on the development of the survey, the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey “gives you a picture on how residents are doing across the state and in neighborhoods specifically, which can help community leaders plan. It really provides a holistic understanding of quality of life, which we know matters, not only in the immediate but over the long term. Capturing things like how do people perceive their community, how do they relate to each other, in addition to economic indicators that are more traditional, really gives us a better sense of not only individual well-being but community well-being, and that is important for ongoing policy and program development.”

Developing a statewide, cross-sector survey on neighborhood well-being

One goal of the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey is to develop robust information on individual- and neighborhood-level well-being that was previously unavailable at the local or even state level. More than 16,000 randomly-selected residents throughout Connecticut participated in in-depth cell phone and landline interviews, providing local partners with information on a range of issues that in many cases can be disaggregated at the local level.

In planning the survey, we were inspired by words of Angela Glover Blackwell, the CEO of PolicyLink, who said at a 2014 OECD/Ford Foundation event, “if you want to achieve an equitable outcome, it starts with disaggregated data. We need to have the courage to look within ourselves and see who is, and who isn't, doing well."

The survey program grows out of a need to unify data collection on social and economic issues throughout Connecticut. DataHaven and a panel of survey research experts began by considering results from more than a dozen local-level surveys conducted throughout Connecticut in recent years, including others by DataHaven, as well as dozens of national surveys. Based on previous studies done elsewhere in the US and significant input from local and national experts, DataHaven developed the questionnaire to serve as a uniform tool for a variety of organizations.

This survey was made possible through the direct support of more than 50 partner organizations and funders, including community foundations, non-profit hospitals, colleges and universities, local public health departments, and other state or regional agencies. Adult participants were recruited by landline and cell phone, and then participated in live interviews in English and Spanish with staff of the Siena College Research Institute. Data was weighted to represent populations in each area, and sample sizes were scaled to match populations in large, midsize, and small cities and towns with all 169 towns included.

Breaking down the data by neighborhood and demographic group

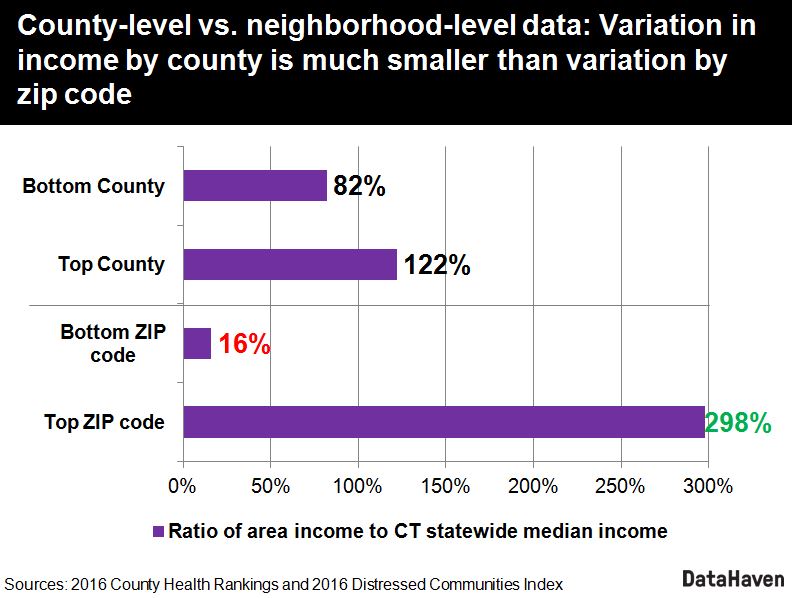

There are differences in median income or health status across counties, but these differences are much more striking when comparing zip codes or neighborhoods within the state’s urban centers and wealthier towns. The survey results highlight the need for better disaggregation of data at a local level, where we see much of the variation occur.

Since the survey was designed to look at neighborhoods, we prioritized neighborhood-level questions on community resilience – such as about the environment surrounding people’s homes. Assets like sidewalks, safe neighborhoods, stores, and parks were among the questions that we felt were important. Survey responses confirmed the importance of these assets – with walkability scales varying widely across different types of built environments.

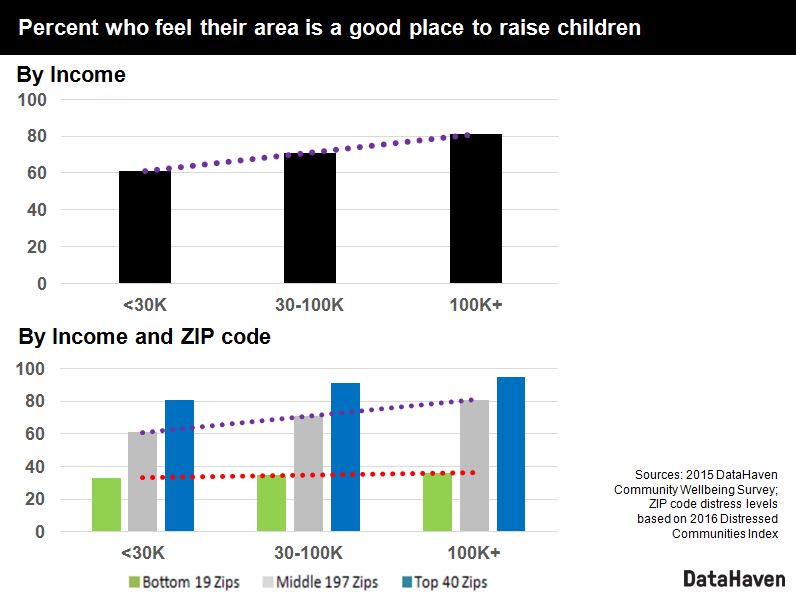

Additionally, we often expect to see differences in well-being across income level. For example, higher income residents are more likely to report that their neighborhood is a good place to raise children. However, the survey allows us to dig deeper and include the effects of neighborhoods themselves.

Splitting this question on age-friendliness by zip codes’ distress levels, we see that neighborhood conditions are a much better predictor of a participant’s answer to this question than their income. Residents in the state’s highly-distressed zip codes, which are primarily in the city centers of Bridgeport, Waterbury, and Hartford, have similar answers regardless of their household income.

This speaks to the importance of disaggregating data at a neighborhood level, especially to understand community context and plan appropriate interventions.

We also see differences when disaggregating by both race/ethnicity and age, as previously mentioned. This is particularly important because the median age of white residents is more than a decade older than that of Latino residents. Calculating differences across age groups is essential to producing a valid picture of community well-being.

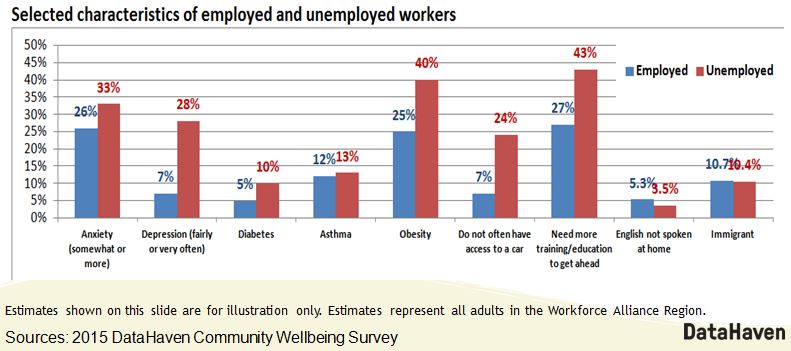

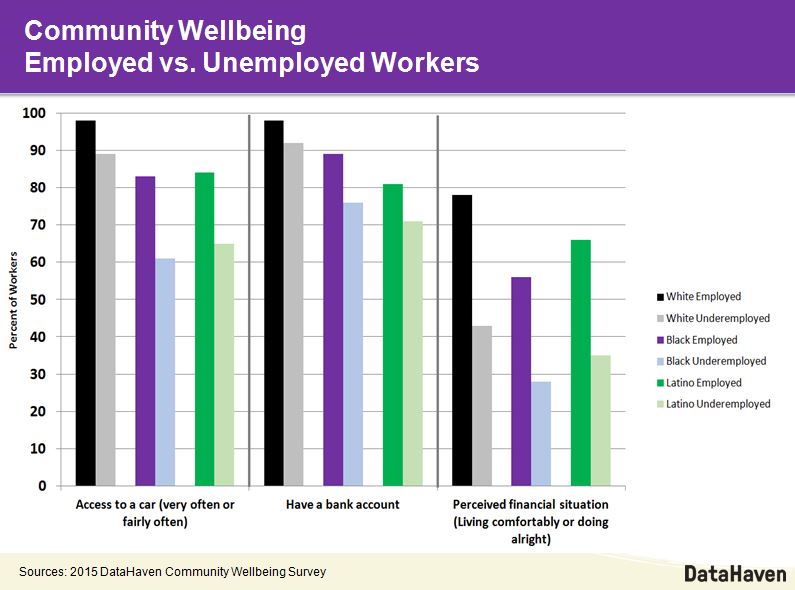

Similarly, we get a more complete picture of both personal and community well-being when we split participants into groups like food insecure versus secure; employed, unemployed, and underemployed; or commute time. For many questions, these groupings—in combination with other demographic factors—tell us much more than income level alone.

With some of these alternative groupings, we can identify differences in access to resources, such as cars, banking, and internet access, that may help organizations and policymakers better understand and target residents’ needs or justify changes in policies that support families.

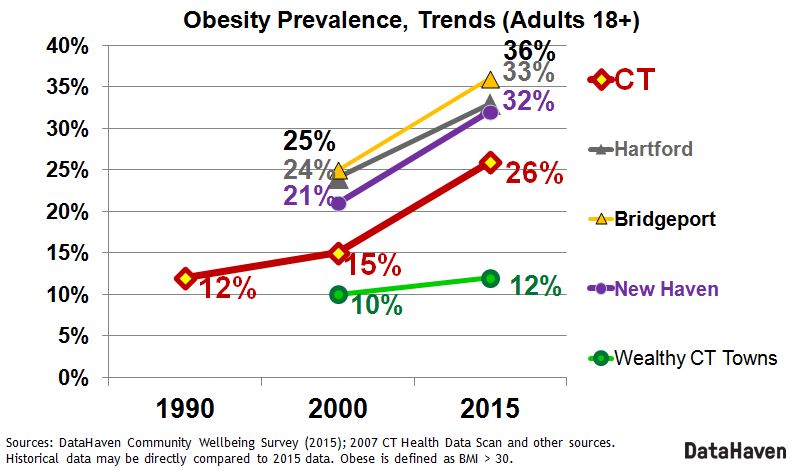

Using consistent questions in multiple survey efforts allows us to measure changes over time as well. For example, obesity prevalence has increased statewide since 1990, but at different rates based on location. Obesity rates stayed steady in wealthy towns, while rising sharply in other parts of the state.

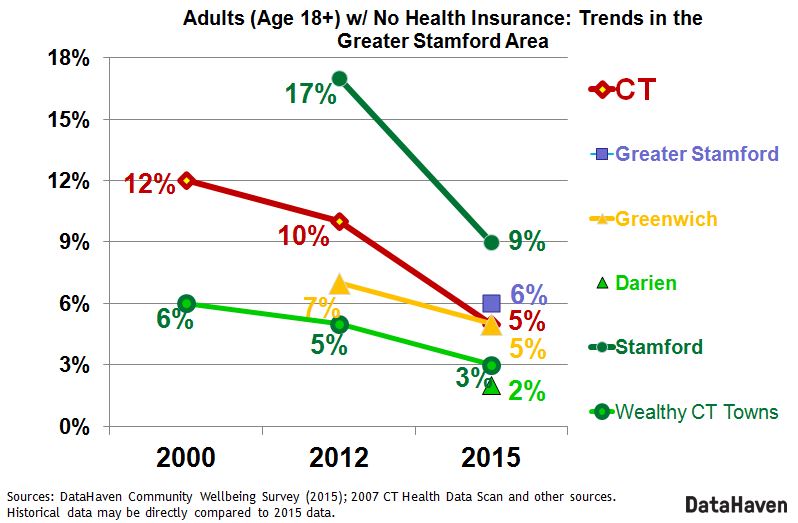

Looking at trends over time within regions, we see wealthier towns are also less likely to smoke regularly. Similarly, while rates of adults lacking health insurance have gone down statewide, we still see rates are high within areas with large populations of immigrants.

We also found differences by location within regions and cities. We compared measures between neighborhoods in large cities, and in some cases mapped data by zip code. Within all regions throughout the state, we found stark differences in a series of health care measures when comparing low-income residents to high-income residents.

Residents in wealthy towns are more likely to have positive opinions on health-promoting community resources, such as the conditions of parks, access to services, and neighborhood safety. At the same time, the survey shows that the most distressed neighborhoods also contain many assets that support community resilience, including walkable sidewalks, bike lanes, cultural activities, and involved neighbors.

Accessing survey resources

On our website, we host resources such as reports and survey crosstabs; we also have developed community profiles for towns and neighborhoods. In the crosstabs, we make available regional and town-level estimates for every question broken down by demographic groups, income, and education, along with guidance for using the tables. Other organizations throughout Connecticut and beyond are making extensive use of the data, and may contact us with any questions.

By working closely with dozens of other organizations throughout Connecticut, we are releasing reports and neighborhood tools based on the survey data and other state and federal data sources. These include several of our own comprehensive community indicator reports focused on the Fairfield County and Greater New Haven areas, that will serve a double purpose as Community Health Needs Assessments for non-profit hospitals and health departments in these regions. We are also building partnerships with media organizations and universities, and providing ongoing technical assistance to non-profit organizations and government agencies throughout the state. We encourage other organizations to use or build upon the survey to better understand local communities’ trends and needs.

DataHaven encourages interested parties to reach out to suggest topics or questions that should be included in the future. We were cautious on this survey to not duplicate other efforts; but designed it in a way that would complement other sources of information that already exist.

A webinar with more information on the DataHaven Community Wellbeing Survey is available on the Public Health Foundation’s TRAIN national website, made possible with a grant from The Robert Wood Johnson Foundation and funding from participating states and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

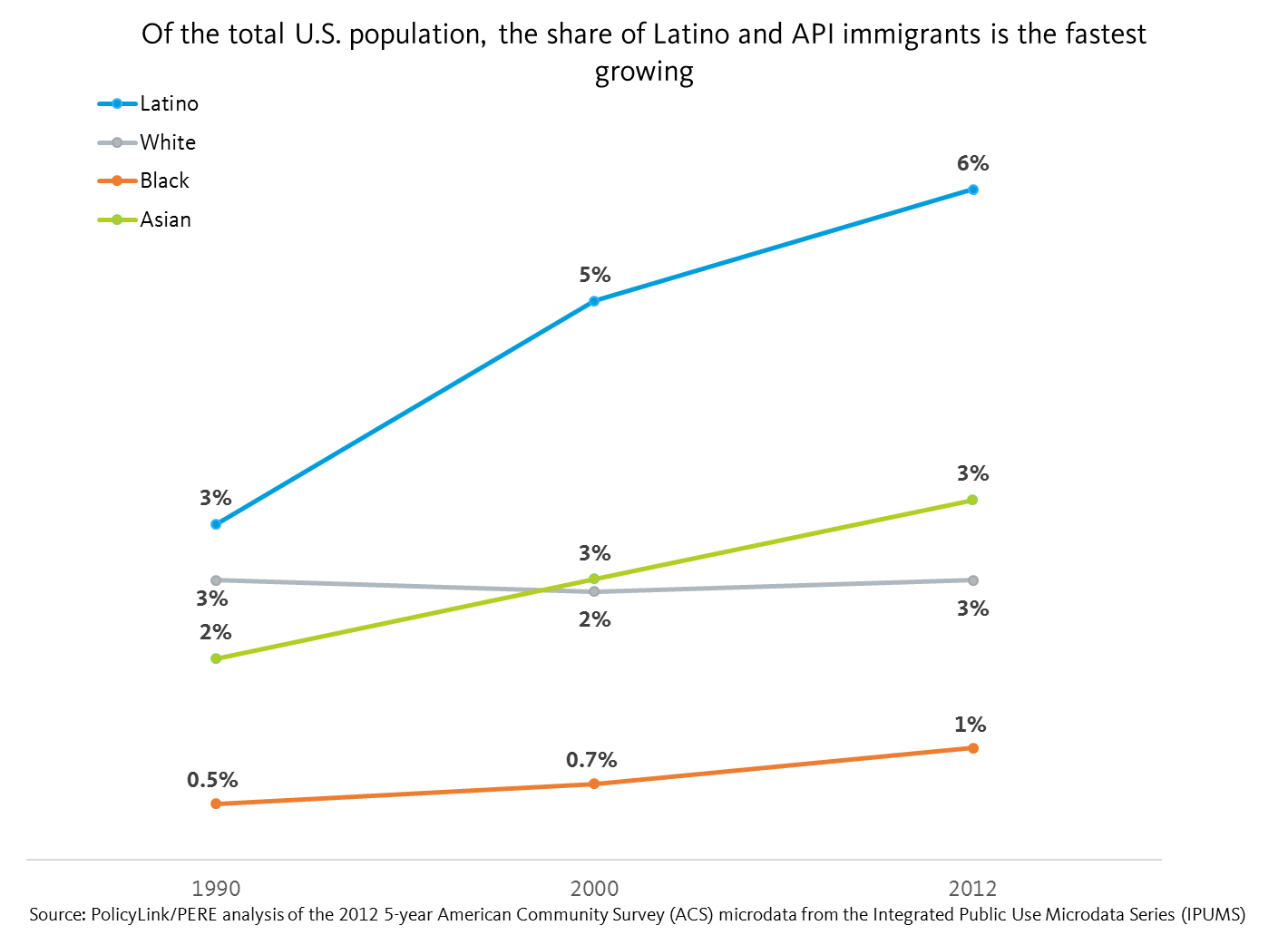

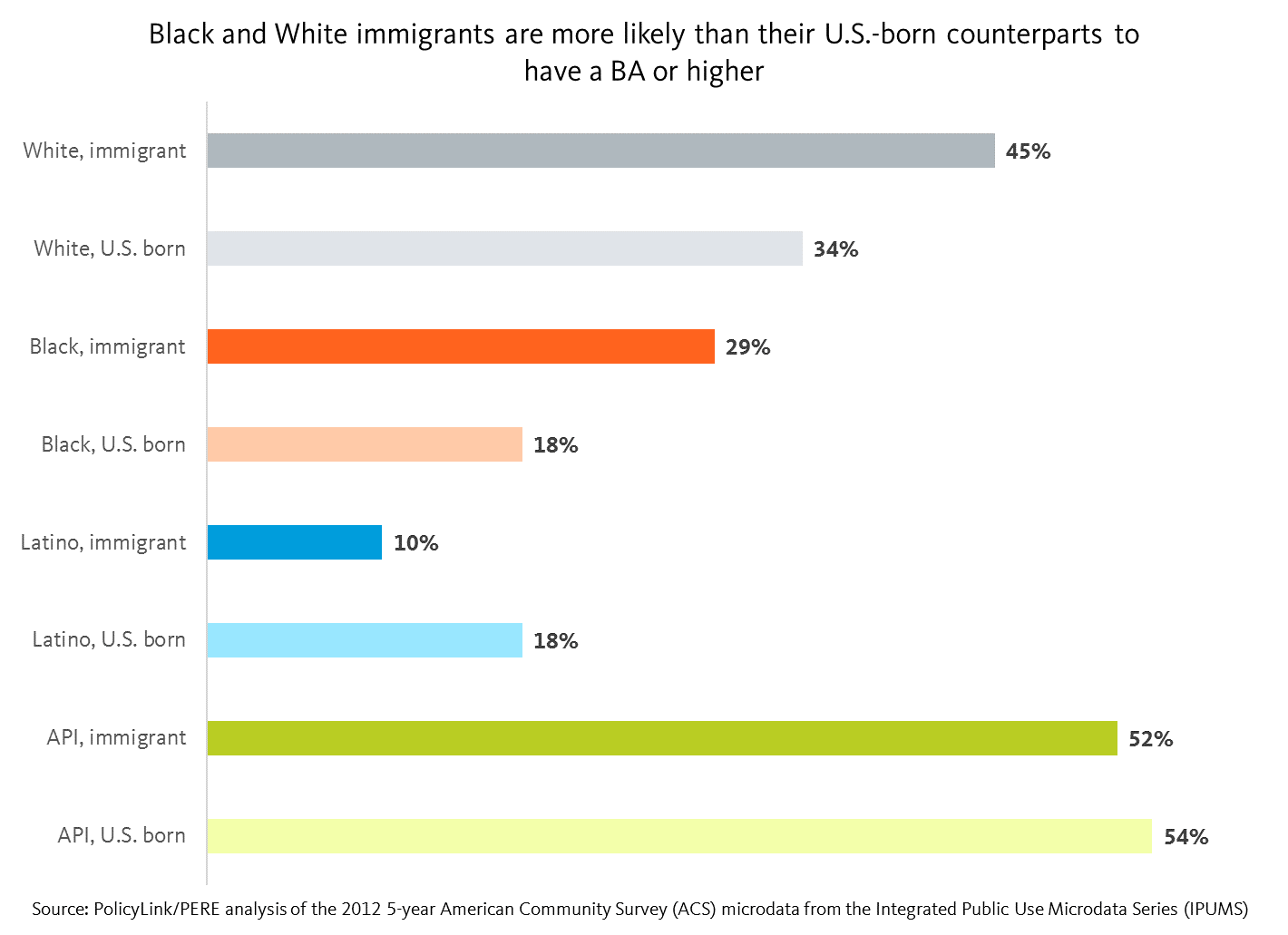

Latino immigrants made up 3 percent of the total U.S. population in 1990, a figure that doubled to 6 percent by 2012. Latino immigrants represent not only the largest share of immigrants in the U.S., but also the fastest growing. The API immigrant community is the second fastest growing and represent 3 percent of the total U.S. population as of 2012. White immigration has more or less stayed stagnant at 3 percent between 1990 and 2012. Finally, Black immigrants make up the smallest share of the total U.S. population at 1 percent, and are not growing as fast as their Latino and API immigrant counterparts.

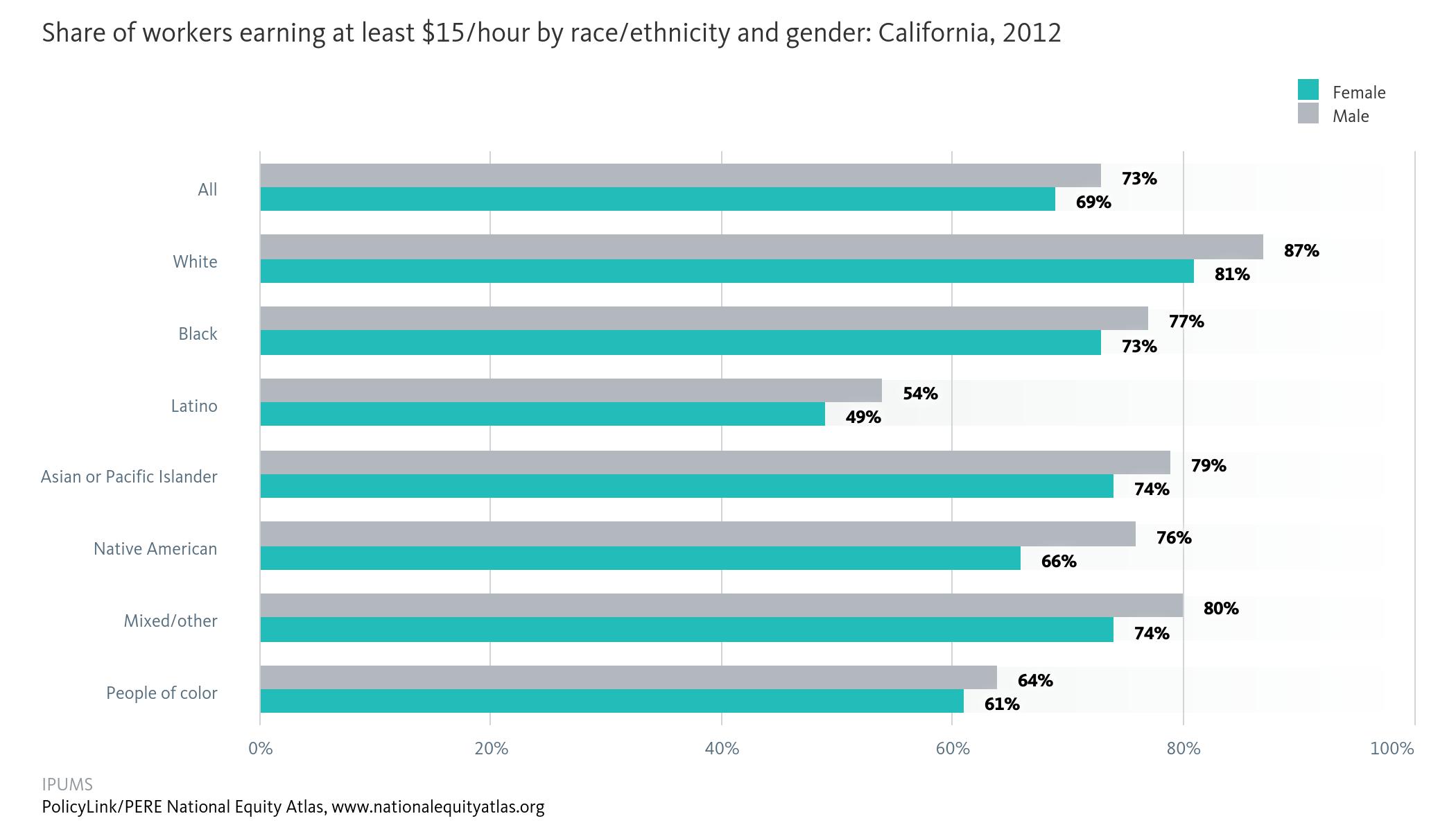

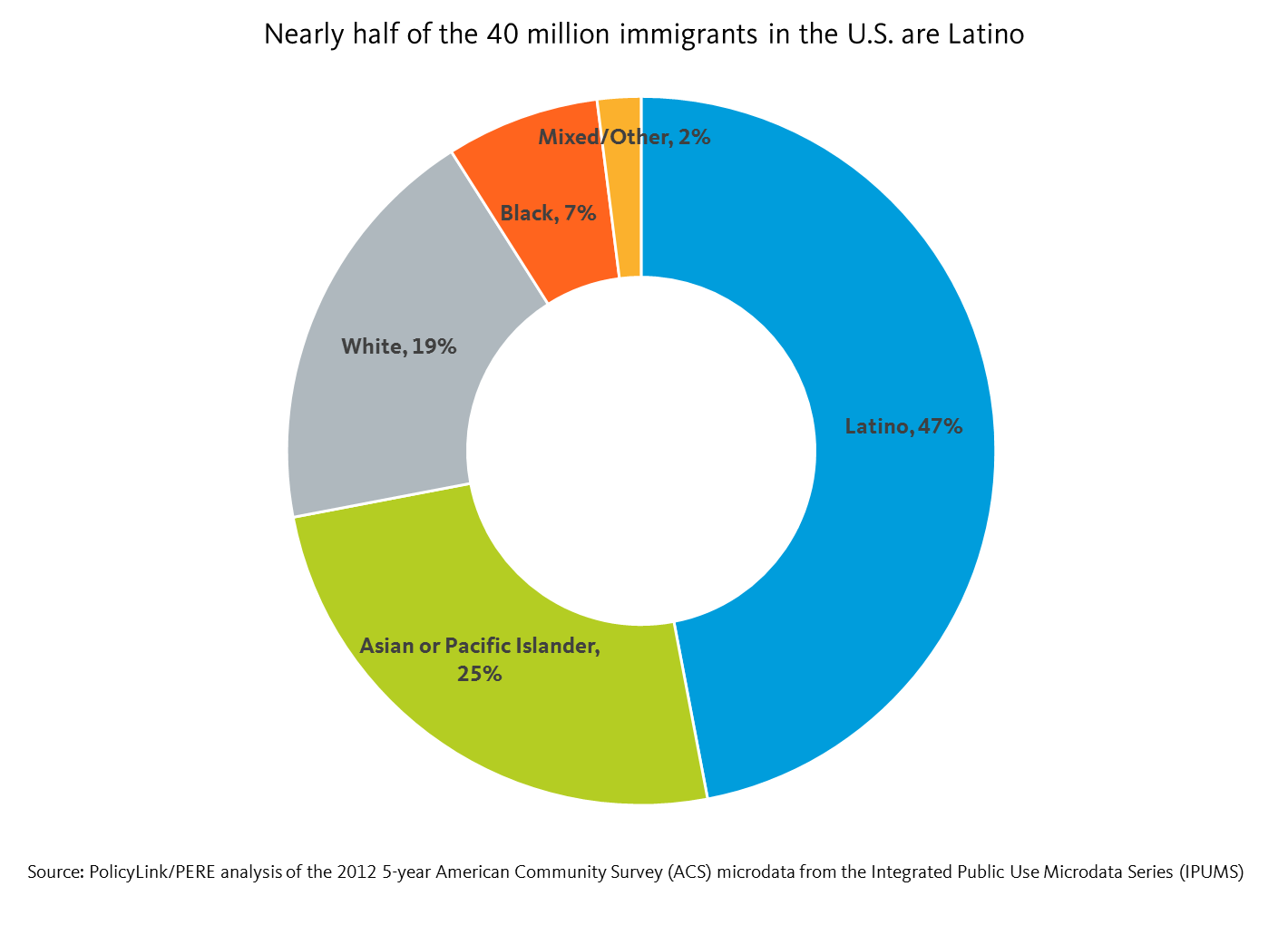

Latino immigrants made up 3 percent of the total U.S. population in 1990, a figure that doubled to 6 percent by 2012. Latino immigrants represent not only the largest share of immigrants in the U.S., but also the fastest growing. The API immigrant community is the second fastest growing and represent 3 percent of the total U.S. population as of 2012. White immigration has more or less stayed stagnant at 3 percent between 1990 and 2012. Finally, Black immigrants make up the smallest share of the total U.S. population at 1 percent, and are not growing as fast as their Latino and API immigrant counterparts. Despite their numbers, Latino immigrants face some of the largest barriers to inclusion. For example, they have the lowest median wage at less than $13/hour, which is $5/hour less than U.S.-born Latinos and half the median wage of White immigrants. Furthermore, 57 percent of Latino immigrants are living under 200 percent of poverty, and 25 percent are working poor.

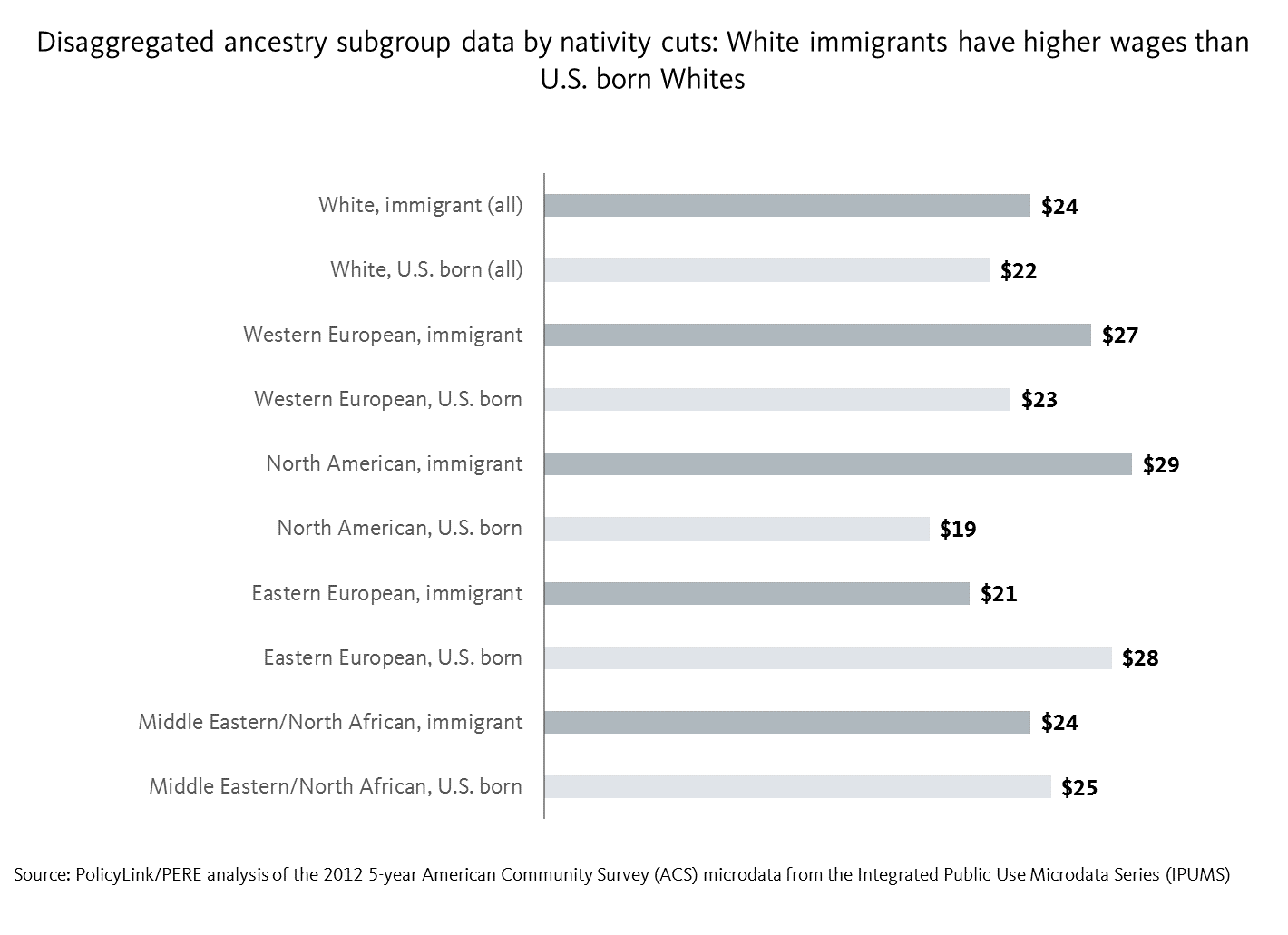

Despite their numbers, Latino immigrants face some of the largest barriers to inclusion. For example, they have the lowest median wage at less than $13/hour, which is $5/hour less than U.S.-born Latinos and half the median wage of White immigrants. Furthermore, 57 percent of Latino immigrants are living under 200 percent of poverty, and 25 percent are working poor. We can do a deeper with-in group analysis by looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by the nativity cuts. For instance, using median wage as an example, immigrant Whites as a whole earn more than U.S. born Whites. Looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by nativity cuts reveals the following: immigrant Whites of Western European and North American ancestry reported lower median wages than their U.S. born counterparts, but immigrant Whites of Eastern European ancestry reported higher median wages than their U.S. born counterparts. On the other hand, immigrant and U.S. born Whites of Middle Eastern/North African ancestry reported the narrowest gap with respect to the disparity in their reported median wages.

We can do a deeper with-in group analysis by looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by the nativity cuts. For instance, using median wage as an example, immigrant Whites as a whole earn more than U.S. born Whites. Looking at the disaggregated ancestry subgroup data by nativity cuts reveals the following: immigrant Whites of Western European and North American ancestry reported lower median wages than their U.S. born counterparts, but immigrant Whites of Eastern European ancestry reported higher median wages than their U.S. born counterparts. On the other hand, immigrant and U.S. born Whites of Middle Eastern/North African ancestry reported the narrowest gap with respect to the disparity in their reported median wages. Studies show the significant economic contributions of Latino immigrants

Studies show the significant economic contributions of Latino immigrants