Gender and Racial Pay Gaps Stifle Local and Regional Economies

Cross-posted from the Toronto Star

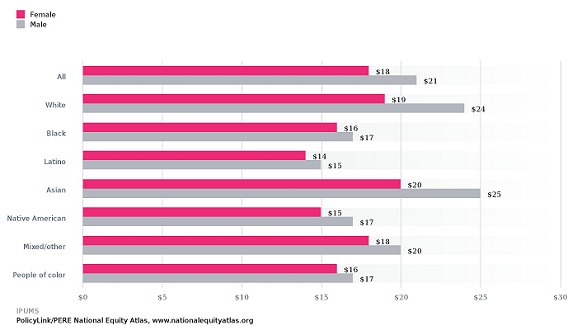

Though they make up nearly half of the workforce in the U.S. and Canada, women — and women of colour in particular — continue to be marginalized in labor markets. Women make significantly less than men of similar experience and education, are vastly overrepresented in low-wage work, and are underrepresented in management — these are not just civil rights issues, they are fundamental failures within the labor market that are holding back economic growth for cities, regions, and entire nations.

When my mother, a young journalist, moved us from her home town of Montreal to New Jersey in the early 1950s, soon after I was born, she was looking for relatively better opportunities to advance in her profession as a woman, and the grass at least appeared to be greener in the States at the time. It did not necessarily turn out to be the case, and both countries still have a long way to go, but there are also promising changes in attitudes and concrete policy steps being taken on both sides of the border, as the imperative for justice intersects in new ways with strong economic incentives for inclusion and fairness.

Urban and regional economies -- in both the public and private sector — have a stake in seeing gender and racial pay gaps decline. As a group, women in the U.S. and Canada are more educated than their male peers and they are the fastest growing demographic of entrepreneurs, with women of colour leading the growth in small-business ownership in the U.S. This, in part, is why many local leaders are doubling down on efforts to address inequities in the workplace, seeking to capitalize on the often underappreciated talent and potential that women in the workforce bring to the table. For example, under the leadership of former Mayor Thomas Menino, Boston sought to become the “premier city for working women”, and current Mayor Marty Walsh recently pledged to become the first U.S. city to eliminate the gender pay gap entirely. Boston is home to the largest proportion of young women between age 20 and 34 — and the highest percentage of college educated women — of any major U.S. city, making the economic opportunity of its young women top priority for local leaders. To close the remaining 18-cent pay gap in the city, Mayor Walsh is leading the charge to educate businesses on the economic importance of closing the gender pay gap. One particular business-focused effort, 100% Talent, is a first-of-its-kind initiative that has enlisted 100 companies to voluntarily pledge to help close the gender gap by sharing payroll data (including metrics on gender and race), implementing recommended practices to reduce pay inequities, and participating in biennial reviews to discuss their progress. The Mayor has also spearheaded a $1.5 million project called Work Smart in Boston, which will provide 90,000 women with salary and benefits negotiation training over the next 5 years.

On the opposite coast, in a city home to the largest gender pay gap among major U.S. cities -- local government in Seattle, Washington is taking inspiration from Boston’s example. After a 2013 analysis found that women in the Seattle metropolitan area were earning 73 percent of what men make, with women of colour earning anywhere from 49 to 60 percent, then-Mayor McGinn’s office convened the City of Seattle’s Gender Equity in Pay Task Force, which has led the city to pass a resolution in 2014 calling on several cities departments, including the Personnel Department, Seattle Office of Civil Rights, and the Mayor’s Office, to promote progressive policies in hiring, pay, and benefits that specifically target both gender and racial inequities. Within the private sector, the city’s Chamber of Commerce and the Women’s Funding Alliance launched their own 100% Talent in 2015 whereby businesses will be obligated to identify internal gender equity issues, share lessons learned with other employers, and implement at least three of the 33 best practices identified by the initiative, including flexible scheduling, greater wage transparency, and increased diversity in hiring practices.

Though these efforts are still in their early stages, these leaders are proving that they understand the crucial opportunity facing cities and regions today: the places that will thrive the most in the 21st century economy will be those that embrace inclusion and capitalize on the talent, creativity, and potential of all residents — especially those who have too often been left behind. This dedication to inclusion is at the heart of All-In Cities — an initiative to promote inclusion and equitable growth in cities launched this year by my organization, PolicyLink.

Like the recommendations made by the 100% Talent initiatives above, All-In Cities seeks to support policymakers and businesses within metropolitan areas to foster comprehensive economic and racial inclusion. For gender and racial inequality in the workplace, this means looking beyond the pay gap to the very structure of the labor market — asking not only, how can we lift stifled wages for women, but how can we build work environments that are conducive to the needs of the ever-growing segment of female workers and their families.

In addition to reevaluating wage, hiring, and scheduling practices as mentioned above, this means policymakers and businesses should foster female entrepreneurship and leadership within organizations. They should promote women’s education and recruitment within high-paying fields — such as math, science, and technology — where they are historically underrepresented. Employers should offer paid family leave and sick leave, so that working mothers do not have to choose between a paycheck and taking care of a sick child.

Overcoming an issue as stubborn as the pay gap will require widespread cultural shifts — in classrooms, in boardrooms, in local councils and halls of parliament —but the rewards we will reap in justice and prosperity are well worth the effort. Advocates for equality from an earlier time, like my mother, would have appreciated how much the ground has shifted.