Named one of Bill Moyers's "19 Young Activists Changing America," Sarita Gupta, executive director of Jobs With Justice, is a driving force for economic and social justice within today's labor movement. Drawn to the labor movement as a student activist at Mount Holyoke College, Gupta has spent her career fighting for the rights and dignity of working people, especially low-wage earners and workers of color.

Under Gupta's direction, Jobs With Justice has helped to win wage increases for 10 million low-income New Yorkers and Californians, secured overtime and wage protection for two million home-care workers, and helped update overtime regulations that affect 12.5 million workers. Gupta also serves as co-director of Caring Across Generations, a national movement working to transform the growing care-giving sector.

Here, Gupta shares her vision for a healthier economy and brighter future through advancing the rights, voice, and power of America's workers.

You began your career in advocacy as a student activist, and you served at the United States Student Association from 1996 to 1998 first as vice president, then as president. How did this early work in education set the stage for your transition into the labor movement?

As a student activist, I witnessed friends and fellow students having to drop out of school because they couldn't afford tuition. I began to see systemic issues at play. You can't achieve educational success without having economic stability, and without attaining a higher level of education, your job options are limited. So, I was moved to get involved and help break this cycle.

During my tenure at the United States Student Association (USSA), I realized that the forces moving an agenda to privatize and corporatize higher education, cut taxes, and limit student voice in shaping policies in their states, were many of the same special interests who stood against the rights and opportunities of working people. It was clear to me that the only way to counter the attacks on students and working people was to build a joint movement.

Given that the fight to increase worker power in the United States is often in opposition to powerful corporate interests, how can advocates meet the challenge of changing the culture of labor in the U.S.?

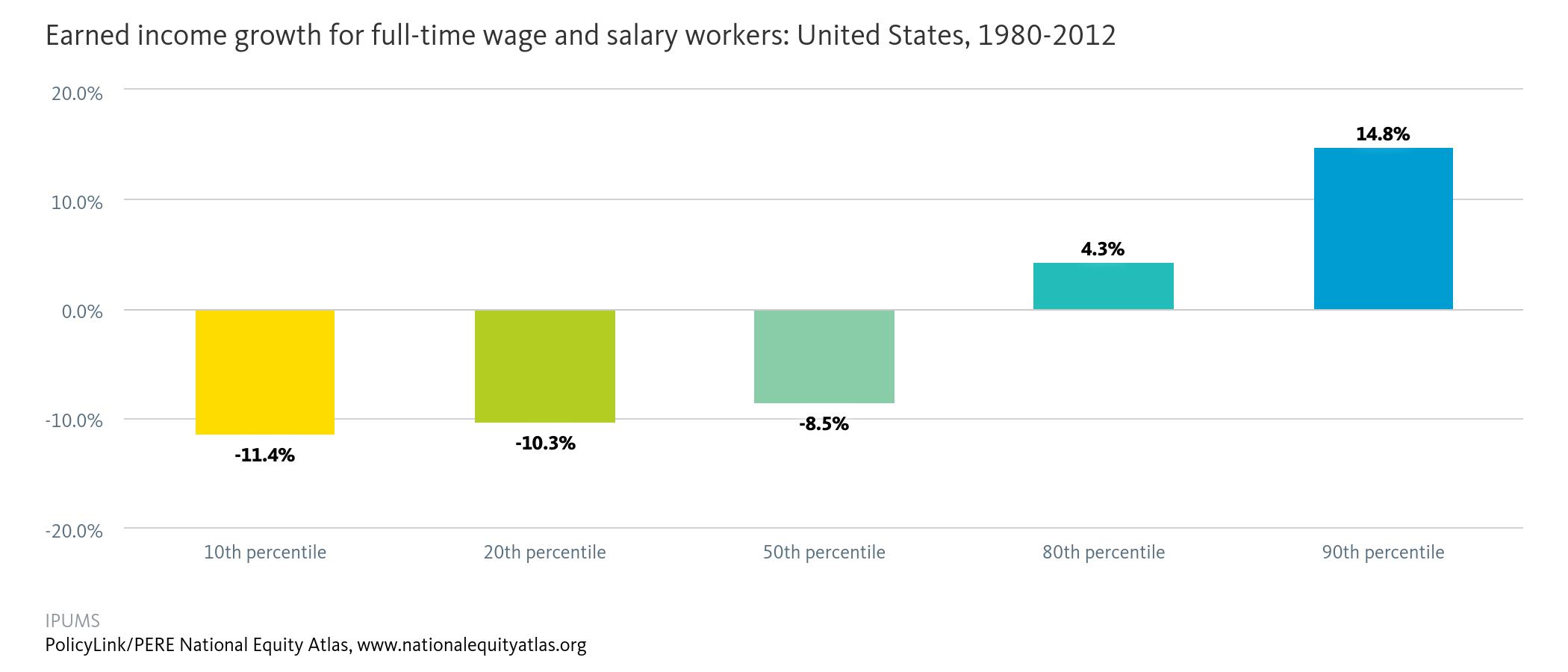

There will always be antagonism between corporate interests and working people's interests, so it's healthy and honest for there to be conflict and differences. And one should be suspect if someone argues otherwise. In the history of the United States, working people have struggled for all the protections that we have earned — from the safety net to child labor laws, to the eight-hour workday. These bedrock protections weren't handed down to Americans out of the charity and benevolence of corporations or our government. Thirty years of neoliberal policy in this country led to corporations holding an extreme concentration of wealth and power. If we are ever going to achieve the type of equity that is necessary and healthy for the economy, we need to shift the balance of power back into the hands of working people and ensure that the voices of unions of working people are respected, as they are in many industrialized nations.

Is it going to be culturally challenging? Of course, but by joining for a common cause, we can have more of a say and negotiate more for ourselves, as well as the next generation. Corporations are not immune from the pressure of a rising tide of public outrage and a groundswell of critique from employees. We also can look to the growing movement of socially responsible business models, like B corporations, as evidence that there are American businesses striving to reconsider their relationship with their employees. They are proving that businesses thrive when they listen to and invest in people who make them successful.

In your opinion, what is the relationship between workers' rights and the overall strength of the economy?

In recent decades, much of the discourse around the economy has focused on the needs of corporate interests, which only addresses one part of the whole economy. As a result, policies that address the economic security of families are often cast as a threat to economic growth. But, if people lack the means to participate in the economy as workers and consumers, then the economy suffers.

At Jobs With Justice, we believe a strong and vibrant national economy is one in which the needs of both families and firms are met. Our economy is off-balance with too much power and money in the hands of too few. When working people can come together and negotiate over the terms and conditions in the workplace, and can have input over their communities, we can rebalance the economy.

How will labor movements help the United States navigate the dual demographic shifts facing our economy: the increasing size of our aging population and the rapidly growing majority of color?

This is an exciting time for our nation. We have the opportunity to write new rules to address the future of our communities, the future of work, and future generations. But by failing to implement solutions, we're allowing some profitable employers to push people of color into low-wage jobs with no opportunity for advancement. Many hardworking moms, dads, and young people aren't earning enough to sustain their families, despite working in booming sectors of society like home care, restaurant and food services, child care, and retail, to name a few.

Thankfully, the growing Fight for $15 and a Union movement, the movement for Black lives, adjunct professors pushing back against poverty wages, and countless other campaigns for change are all fueling the demands for a better life and a new social contract.

Given the growth of our aging population, we're in the midst of an unprecedented boom in the need for care providers. At the same time, the baby boomers are living longer than any previous generation, thanks to advances in technology and health care. While care is the work that makes all other work possible, caregivers like nannies and home care aides who look after our elders and children work under strenuous, highly vulnerable conditions, while earning poverty wages.

We have a tremendous opportunity to meet the soaring need for high-quality caregivers and ensure these jobs are good jobs — ones that offer stability and opportunity for the millions of people who do this work every day. To meet that challenge, the campaign I co-created called Caring Across Generations, is mobilizing millions of people to place care at the forefront of the national conversation, and move policies that make care affordable and accessible.

As grassroots organizations work to shape U.S. workforce policies, how should they decide where to focus their energy?

Deploying energies locally would be smart, as generally, we have the most opportunity to win at the state and municipal level. Local wins are foundational. By winning a new policy demand, organizations can set in motion more change by inspiring other communities to follow suit and demonstrate what's possible. Regardless of the gridlock in DC, the campaigns that are most transformative have been focused locally, modeled a new policy approach, and built momentum across the country.

For example, we led the charge with Jobs With Justice San Francisco to enact the first set of comprehensive and meaningful standards to address unstable work schedules and stop employers from assigning employees too few hours on too short notice, which jeopardizes their ability to provide for their families. Now 40,000 people who work in large retail and restaurant establishments in San Francisco have stronger guarantees of a fair and consistent schedule. Our friends at Working Washington were coordinating and learning lessons from us as they mounted a similar campaign, and just last month the Seattle City Council passed their robust scheduling legislation, which the mayor has committed to signing.

Grassroots organizations also should focus their energies on shaping the public conversation about the policies they want to enact. Grassroots groups and policy groups too often fall back on doing what they know best — talking to their bases and constituencies in the language that speaks to them. It's not enough. We have to build the muscle of connecting with people who aren't already on board with us.